Prp Injection for Rotator Cuff How Do You Know if You Are Healing

Abstract

The prevalence of the rotator cuff (RC) tears is ~ 21% in the full general population, with college incidences in individuals over fifty. Irrespective of surgical repair techniques employed, re-tear rates are alarmingly high, indicating the need for comeback to the current handling methods. A method that has recently increased in popularity is the administration of platelet-rich-plasma (PRP), every bit it has been proposed to significantly encourage and improve healing in a plethora of musculoskeletal tissues, although experimental conditions and results are ofttimes variable. This review aims to critically evaluate electric current literature concerning the use of PRP, specifically for the treatment of RC tears. There are ongoing conflicts debating the effectiveness of PRP to care for RC tears; with literature both in favour and against its use either having profound methodological weaknesses and/or limited applicability to most individuals with RC tears. There are numerous factors that may influence effectiveness, including the subgroup of patients studied and the timing and method of PRP delivery. Thus, in club to define the clinical effectiveness of PRP for RC tears, the training protocol and composition of PRP must be standardised, then an accurate assessment and comparisons can be undertaken. Prior to clinical realisation, at that place is a requirement for a defined, standardised, quality-controlled protocol/procedure considering composition/formulation (of PRP); injury severity, dosage, frequency, timings, controls used, patient group, and rehabilitation programmes. Nevertheless, it is concluded that the initial stride to aid the progression of PRP to care for RC tears is to standardise its preparation and commitment.

Introduction

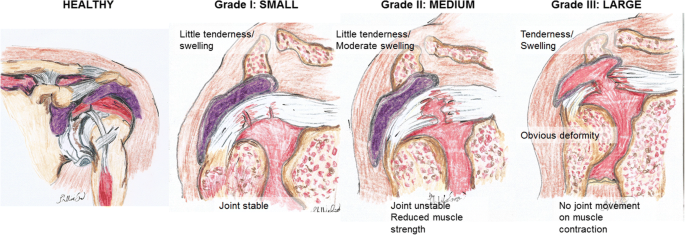

Rotator cuff (RC) tears (Fig. 1) are i of the near mutual causes of shoulder pain, usually leading to difficulty sleeping and poor function [1,ii,iii]. The prevalence of RC tears is approximately 21% in the general population, which increases with age [iv,5,6,seven]; with considerably more than tears sustained by individuals anile 50 and older [8]. RC tear risk factors include degenerative changes to the tendon, traumatic injury, genetic predisposition and repetitive shoulder impingement [4, nine,10,11]. Both non-operative [12, 13] and operative treatments/therapies [fourteen] can exist used for RC tears, with detailed studies published comparing which strategy is the most constructive [xv, 16], but surgery may often be the only option for some patient subgroups. Despite advancements in surgical techniques, there is even so an alarming tendon re-tear rate, ranging from 15 to 40% regardless of the surgical technique employed [1, 17, 18]. Therefore, operative methods of treating RC tears require pregnant optimisation to reduce secondary re-tears.

Salubrious shoulder, pocket-size RC tear, medium-large RC tear, consummate RC rupture (large tear)

The volume of research aimed at improving clinical outcomes post-surgery has increased considerably in recent years, leading to advances in surgical methods and techniques, along with enhancements in rehabilitation programmes [nineteen,twenty,21]. For case, a recent development has been the increasing use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) as a novel method of treatment for musculoskeletal injuries. Sengodan et al. (2017) suggested that PRP can reduce the pain caused by tendon tears, while accelerating the healing process and lessening all-encompassing rehabilitation time [22]. PRP theoretically accelerates tendon healing by increasing revascularisation at the injury site. It is widely understood that PRP contains a high concentration of platelets, which are a rich source of numerous types of growth factors with restorative properties [22,23,24,25]. Numerous clinical studies have discovered that PRP enhanced RC tear repair and concluded that PRP has the potential to improve standard RC tear repair methods [26,27,28]. Conversely, many clinicians do not support the employ of PRP in RC repair, every bit it failed to amend the RC healing process or re-tear rates when compared with control patients [29]. Furthermore, Carr et al. (2015) claimed that PRP may even have a detrimental long-term effect on the structural properties of the tendon [30]. Thus, the aim of this narrative review is to critically evaluate the literature to assess the effectiveness of PRP as a treatment method for RC tears in order to provide explanations for the frequent conflicting findings within published studies.

PRP Preparation Methods and Composition

In general, PRP preparation involves the drove of 20–60 mL of claret from the patient; anticoagulant is then added prior to centrifugation using a two-stride process in order to concentrate and divide out the platelets [31]; two–6 mL of PRP is extracted and activated using agents such as thrombin to induce the release of platelet growth factors and polymerisation of fibrinogen into fibrin [32], followed by an injection of the full-bodied PRP into the patient [33].

Chahla et al. (2017) conducted a systematic review into the composition and grooming protocols of PRP in 105 different clinical studies when used to care for musculoskeletal conditions [34]. It was revealed that just ten% of the published studies provided enough information regarding the preparation protocol that would enable their methods to be repeated. Also, only xvi% of studies reported sufficient data on the composition of the PRP samples. Thus, despite the widespread utilise of PRP, inadequate information is provided regarding PRP training protocol and formulations. Confusion regarding the terminology used to ascertain, classify, and depict variations in platelet concentrations farther exacerbates the variation and apparent lack of quality controls in reported protocols. Thus, Ehrenfest et al. (2009) proposed four families of PRP based upon cell content and fibrin architecture [35] (Tabular array 1). However, in that location is even so a requirement for the development of standardised PRP preparation protocol, and composition is essential for assessing its effectiveness every bit a treatment for musculoskeletal weather [34, 36, 37]. Standardisation would also enable direct comparisons between studies to be made and successful studies to be reproduced with ease if required. Standardisation of the protocol and composition of PRP would allow researchers to make up one's mind whether PRP is an integral component of the treatment for RC tears, which currently remains controversial.

Word

PRP Treatment for RC Tears

PRP is increasingly used in a clinical environment since information technology enables the localised delivery of cellular and humeral mediators that accelerate the healing procedure [38]. Chahla et al. (2017) proposed that lenient regulations for the clinical assistants of PRP are a potential crusade of its recent rise in popularity within musculoskeletal medicine [34], including the direction of knee osteoarthritis [33].

Despite these leniencies, the optimal dose range of PRP is nevertheless to be established [39]. A possible caption for this could be that at that place is a considerable amount of individual variation in the claret concentration of platelets and growth factors [forty, 41]. Furthermore, there are both surgical- and patient-specific factors that may bear upon RC healing that have been previously reviewed past Menon et al. (2019). These include RC chronicity, co-morbidities, previous repair techniques employed, suturing techniques, follow-up and post-operative rehabilitation; patient historic period and lifestyle (run a risk factors include smoking, loftier cholesterol, and diabetes). An boosted cistron that needs addressing is the divergence in the preparation protocol of PRP which go far difficult to directly compare individual studies and to definitively appraise the influence of PRP on the healing procedure [42]. This may provide a legitimate explanation for the conflicting findings inside the literature regarding PRP equally an constructive treatment method for RC tears.

Critique of the Clinical Effectiveness of PRP for Treatment of RC Tears

Researchers and clinicians are currently divided as to whether PRP should be involved in RC tear treatment, with conflicting clinical outcomes published in the literature. The reported benefits and potential detrimental effects of PRP will be discussed in the post-obit sections.

Favourable Benefits of PRP for RC Healing

PRP is attractive in that it offers an alternative to conventional surgery corticosteroid injections [43] and/or in instances where conservative treatments take failed. The proposed role of PRP is to decrease pain and inflammation while stimulating healing [44]. Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, information technology has been theorised that the release of growth factors in combination with high concentrations of activated platelets stimulates and promotes musculus and tendon healing and growth [45, 46]. In some instances, the benefit has been reported to exist cost-effective with prolonged hurting management and lower take chances of adverse side effects compared with conventional treatments [22].

Rha et al. (2013) conducted an investigation comparing the effects of PRP injections with dry out needling treatment in 39 patients with either supraspinatus tendinosis or a tear smaller than i.0 cm [47]. Dry out needling refers to a technique which utilises thin monofilament needles which are inserted without the use of injectate; although often associated with intramuscular pain, it can too be practical to the ligaments, tendons, fascia, scar tissue, neurovascular bundles, and within the vicinity of peripheral fretfulness to manage pain [48]. The report reported that the PRP injections were more than effective at reducing pain and disability compared with dry needling. The advantageous impact of PRP-treated supraspinati was reported to be nonetheless evident half-dozen months following the procedure, indicating that PRP injections are a rubber and suitable prolonged treatment method of treating RC injury, at to the lowest degree for the direction of small RC tears.

More than recently, Jo et al. (2015) demonstrated that PRP treatment can improve the quality of the repair in patients with medium or large RC tears (Fig. 1). This was supported past a significantly lower re-tear rate (P = 0.032) and increased cantankerous-exclusive area of the supraspinatus (P = 0.014) in the PRP-augmented repair group when compared with a conventional treated group [49]. However, no significant differences in healing rate, flexibility, musculus strength, function, and pain scores betwixt groups were identified.

Sengodan et al. (2017), all the same, did ostend a reduction in patient pain scores with improved shoulder role at 8 and iii months post-obit treatment with ultrasound guided PRP injections. As the authors indicated, there were many strengths of this investigation, including that function and pain scores were obtained at frequent fourth dimension intervals and an impressively high follow-upwards rate of 91% was seen at 8 weeks. However, it should exist noted that the follow-upwardly time period of 8 weeks is relatively short when compared with similar studies and was arguably too short to assess the prolonged effectiveness of PRP injections for RC repair.

Unfavourable Furnishings of PRP for RC Healing

Despite the reported aforementioned benefits of PRP, the evidence is predominantly anecdotal and/or lacking scientific rigour and the bulk of authors are unable to written report significant advantages in randomised clinical trials with more prolonged follow-up periods [50]. In a recent meta-analysis, Fu et al. (2017) concluded that no departure in pain and disability outcomes could be distinguished when comparing patients treated using PRP or a platelet-rich fibrin matrix and those who were treated conventionally [51]. Yet, just a small number of studies were included in the analysis and a wide variation between studies was evident [51]. This ultimately reduced the power the analysis provided. The authors best-selling this and conceded that the pain scores included in the summary of PRP'southward effectiveness may non correlate with the severity of the RC tear, thus limiting the conclusions drawn.

Akin to Fu et al. (2017), Charousset et al. (2014) also reported no divergence in tendon healing quality betwixt patients who had leucocyte-PRP injections during their arthroscopic repair of big RC tears and those that did not based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluations [52]. The authors do acknowledge that a reduced re-tear rate has been discovered in PRP-treated patients with small and medium tears in previous investigations [53]. Similarly, Castricini et al. (2011) failed to constitute any enhancements in the healing of small or medium RC tears treated arthroscopically with the administration of PRP [54]. These studies indicate the complication of encountering definitive clinical evidence on the value of PRP in enabling an improved recovery from RC tears. Farther clinical trials utilising PRP specifically for RC injuries are presented in Table 2 (modified from Dickinson and Wilson 2018 [28]).

Every bit formerly mentioned, PRP may potentially accept a negative long-term impact on tendon structure that increases tear susceptibility [30]. Carr et al. (2015) investigated the clinical and tissue effects following the co-application of PRP injection with arthroscopic acromioplasty compared with arthroscopic acromioplasty alone. It was reported that the co-awarding had no significant clinical benefit and most significantly detrimentally altered the tendon tissue and cellular backdrop. Yet, this study was conducted solely on patients with chronic symptoms that had previously failed to reply to bourgeois treatments prior to the study [thirty]. Furthermore, the mean age of the patients was 52.2 years. Another limitation of this study is that there were variations in the preparation of PRP and compositions which ultimately make the clinical benefit of PRP difficult to compare between patients. Carr et al. (2015) acknowledged that the absence of a well-established optimal dose for PRP did limit the power of their written report. Therefore, the estimation made past the authors that PRP has a detrimental effect on RC repair and tendon construction may be somewhat biased, equally the treatment was less probable to succeed in this item subgroup of patients.

Factors Influencing the Upshot of PRP Treatments

There are a plethora of explanations that may influence the effectiveness of PRP as a handling for RC tears that may partially explain the opposing prove presented in published studies. Bergeson et al. (2012) proposed that PRP concentrations and delivery, forth with the subgroups of patients studied, are factors which if optimised could lead to considerable clinical enhancements [29]. For example, repeat administrations and the use of scaffolds for sustained delivery of PRP may inevitably provide more than benefits compared with a unmarried dose for more serious RC tears. Charousset et al. (2014) advocated that additional PRP injections 3 weeks into the recovery period may improve RC tendon healing efficiency as this was the instance for chronic tendinopathies in past studies [52]. Additionally, Barber et al. (2011) concluded that using ii PRP fibrin matrices instead of i led to a decline in RC re-tear rate based on MRI information [61]. Therefore, these studies reiterate that PRP concentrations and the timing of its administration are probable to have a major impact on the success of PRP treatment for RC tears.

Barber et al. (2011) highlighted the substantial disparities in PRP preparation methods; these include the type of anticoagulants used and whether leucocytes are included [61]. The presence of leucocytes has been well debated amidst researchers as it has formerly been recognised that PRP products without leucocytes are less effective at preventing infections developing at the injury site [29]. Information technology has as well been proposed that the addition of leucocytes to PRP could take a negative effect on healing every bit there will exist more neutrophils nowadays in the RC, leading to the production of more reactive oxygen species that kill both healthy and injured cells. The inclusion or exclusion of leucocytes in PRP seems to have a large begetting on its effectiveness regardless of the potential reduction in infection risk or the damaging consequences of neutrophils [62,63,64,65]. Given these inconsistent training approaches and compositions for PRP, farther investigations are essential and so that the optimal methods and concentrations can be established for the use of PRP to treat RC tears.

Conclusion

Advancements in RC tear treatment are required imminently as the current re-tear rate is alarmingly high. PRP assistants has shown promise in enhancing RC tear healing in numerous studies, although drawbacks of these studies have been well documented in this review. To accurately appraise PRP's result on the healing of RC tears, future inquiry should aim to standardise PRP's preparation and composition. The factors identified are likely to also have a begetting on the clinical efficacy of PRP. Prior to clinical realisation, there is a requirement for a defined, standardised, quality-controlled protocol/procedure considering composition/formulation (of PRP); injury severity, dosage, frequency, timings, controls used, rehabilitation programmes, and patient groups. Thus, in add-on to protocol standardisation, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria including age, injury blazon, severity, and co-morbidities need consideration. Merely then can nosotros definitively resolve whether PRP aids the healing of RC tears. If hereafter investigations confirm PRP'due south usefulness, then research can exist initiated to determine the optimum training methods and limerick.

Unfortunately, the existing evidence researchers are basing their conclusions on is somewhat bias or has express applicability to the bulk of patient subgroups. However, it is concluded that the initial footstep to aid the progression of PRP to treat RC tears is to standardise its preparation and utilise.

References

-

Gowd AK, Cabarcas BC, Frank RM, Cole BJ. Biologic augmentation of rotator cuff repair: the role of platelet-rich plasma and bone marrow aspirate concentrate. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2018;26:48–57.

-

Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: cess, management and uncertainties. Man Ther. 2015;23:57–68.

-

Jaeger Yard, Izadpanah Chiliad, Südkamp NP. Rotator cuff tears. In: Arnold Due west, Ganzer U, editors. Bone Jt Inj. Berlin: Springer; 2014. p. 1–11.

-

Yamamoto A, Takagishi G, Osawa T, Yanagawa T, Nakajima D, Shitara H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2010;xix:116–20.

-

Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8:296–nine.

-

Worland RL, Lee D, Orozco CG, SozaRex F, Keenan J. Correlation of age, acromial morphology, and rotator cuff tear pathology diagnosed by ultrasound in asymptomatic patients. J Due south Orthop Assoc. 2003;12:23–6.

-

Robinson PM, Wilson J, Dalal S, Parker RA, Norburn P, Roy BR. Rotator cuff repair in patients over 70 years of historic period. Bone Articulation J. 2013;95-B:199–205.

-

Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, Lee JH, Kang SB, Lee JH, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort written report. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2082–ninety.

-

Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Abe H, Fukuda 1000, Seki North, Kikuchi Thou, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: from mass-screening in i hamlet. J Orthop. 2013;10:8–12.

-

Chung SW, Oh JH, Gong HS, Kim JY, Kim SH. Factors affecting rotator cuff healing afterwards arthroscopic repair: osteoporosis every bit one of the independent risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2099–107.

-

Longo UG, Berton A, Papapietro N, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Rotator Cuff Tear. 2011:i–9.

-

Edwards P, Ebert J, Joss B, Bhabra G, Ackland T, Wang A. Practice rehabilittaion in themanagemenr of non-operative rotator gage tears: a review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11:279–301.

-

Boorman RS, More KD, Hollinshead RM, Wiley JP, Mohtadi NG, Lo IKY, et al. What happens to patients when we exercise not repair their cuff tears? V-year rotator gage quality-of-life alphabetize outcomes post-obit nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2018;27:444–eight.

-

Deprés-tremblay G, Chevrier A, Snow Grand, Hurtig MB, Rodeo S, Buschmann Md. Rotator cuff repair: a review of surgical techniques, animal models, and new technologies under development. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25:2078–85.

-

Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila KT, Tuominen EKJ, Kauko T, et al. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with ii years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Am Vol). 2014;97:1729–37.

-

Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJAM, Koorevaar RCT, van Eerden PJM, Westerbeek RE, van 't Riet E, et al. Comparison surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator gage tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2015;24:1274–81.

-

Miller BS, Downie BK, Kohen RB, Kijek T, Lesniak B, Jacobson JA, et al. When do rotator gage repairs fail? Serial ultrasound examination after arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2064–70.

-

Neyton Fifty, Godenèche A, Nové-Josserand L, Carrillon Y, Cléchet J, Hardy MB. Arthroscopic suture-bridge repair for minor to medium size supraspinatus tear: healing rate and retear pattern. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2013;29:10–seven.

-

van der Meijden OA, Westgard P, Chandler Z, Gaskill TR, Kokmeyer D, Millett PJ. Rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: current concepts review and evidence-based guidelines. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:197–218.

-

Gallagher BP, Bishop ME, Tjoumakaris FP, Freedman KB. Early versus delayed rehabilitation following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:178–87.

-

Ainsworth R. Physiotherapy rehabilitation in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Musculoskelet Intendance. 2006;4:140–51.

-

Sengodan Five, Kurian S, Ramasamy R. Treatment of partial rotator cuff tear with ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2017;7:1–32.

-

Eppley BL, Woodell JE, Higgins J. Platelet quantification and growth factor analysis from platelet-rich plasma: implications for wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1502–viii.

-

Boswell SG, Cole BJ, Sundman EA, Karas Five, Fortier LA. Platelet-rich plasma: a milieu of bioactive factors. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2012;28:429–39.

-

Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, Dragoo JL. Contents and formulations of platelet-rich plasma. Oper Tech Orthop. 2012;22:33–42.

-

Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, Kim H, Chai JW, Jeong EC, et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the genu: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1254–66.

-

Hurley ET, Lim Fat D, Moran CJ, Mullett H. The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin in arthroscopic rotator gage repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:753–61.

-

Dickinson M, Wilson SL. A critical review of regenerative therapies for shoulder rotator cuff injuries. SN Compr Clin Med. 2019;1:205–fourteen.

-

Bergeson AG, Tashjian RZ, Greis PE, Crim J, Stoddard GJ, Burks RT. Effects of platelet-rich fibrin matrix on repair integrity of at-hazard rotator gage tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;twoscore:286–93.

-

Carr AJ, Murphy R, Dakin SG, Rombach INES, Wheway KIM, Watkins B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection with arthroscopic acromioplasty for chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2891–seven.

-

Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Bielecki T, Mishra A, Borzini P, Inchingolo F, Sammartino One thousand, et al. In search of a consensus terminology in the field of platelet concentrates for surgical apply: platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), fibrin gel polymerization and leukocytes. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:1131–seven.

-

Mosesson MW, Siebenlist KR, Meh DA. The structure and biological features of fibrinogen and fibrin. Ann North Y Acad Sci. 2001;936:11–30.

-

O'Connell B, Wragg NM, Wilson SL. The utilize of PRP injections in the direction of knee osteoarthritis. Jail cell Tissue Res. 2019;376:143–52.

-

Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, Mannava Due south, Geeslin AG, Murray IR, et al. A phone call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: a systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg (Am Vol). 2017:1769–79.

-

Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–67.

-

Fadadu PP, Mazzola AJ, Hunter CW, Davis TT. Review of concentration yields in commercially available platelet-rich plasma (PRP) systems: a phone call for PRP standardization. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019:rapm-2018-100356.

-

Oudelaar BW, Peerbooms JC, Huis in 't Veld R, Vochteloo AJH. Concentrations of blood components in commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems: a review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:479–87.

-

Mckee H, Beattie K, Lau A, Wong A, Adachi R. Novel imaging modalities in the diagnosis and risk stratification of osteoporosis. J Orthop Ther. 2017;2017:1–9.

-

Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009:2259–72.

-

Evanson JR, Guyton MK, Oliver DL, Hire JM, Topolski RL, Zumbrun SD, et al. Gender and age differences in growth factor concentrations from platelet-rich plasma in adults. Mil Med. 2014;179:799–805.

-

Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Chowaniec DM, Cote MP, Romeo AA, Bradley JP, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs co-ordinate to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Ser A. 2012;94:308–16.

-

Dhurat R, Sukesh Yard. Principles and methods of grooming of platelet-rich plasma: a review and author's perspective. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:189–97.

-

Schneider A, Burr R, Garbis Northward, Salazar D. Platelet-rich plasma and the shoulder: clinical indications and outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018:593–7.

-

Shams A, El-Sayed 1000, Gamal O, Ewes Westward. Subacromial injection of autologous platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid for the treatment of symptomatic partial rotator gage tears. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:837–42.

-

Sheth U, Dwyer T, Smith I, Wasserstein D, Theodoropoulos J, Takhar S, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma lead to earlier return to sport when compared with bourgeois treatment in acute muscle injuries? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2018;34:281–288.e1.

-

Ebert JR, Wang A, Smith A, Nairn R, Breidahl Westward, Zheng MH, et al. A midterm evaluation of postoperative platelet-rich plasma injections on arthroscopic supraspinatus repair: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2965–74.

-

Rha DW, Park GY, Kim YK, Kim MT, Lee SC. Comparing of the therapeutic furnishings of ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma injection and dry out needling in rotator cuff illness: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:113–22.

-

Dunning J, Butts R, Mourad F, Young I, Flannagan S, Perreault T. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19:252–65.

-

Jo CH, Shin JS, Shin WH, Lee SY, Yoon KS, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of medium to large rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2102–10.

-

Malavolta EA, Gracitelli MEC, Ferreira Neto AA, Assunção JH, Bordalo-Rodrigues M, de Camargo OP. Platelet-rich plasma in rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2446–54.

-

Fu CJ, Sun JB, Bi ZG, Wang XM, Yang CL. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma and fibrin matrix to assist in healing and repair of rotator cuff injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:158–72.

-

Charousset C, Zaoui A, Bellaïche 50, Piterman Thou. Does autologous leukocyte-platelet-rich plasma improve tendon healing in arthroscopic repair of large or massive rotator cuff tears? Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2014;30:428–35.

-

Zhang Q, Ge H, Zhou J, Cheng B. Are platelet-rich products necessary during the arthroscopic repair of total-thickness rotator cuff tears: a meta-assay. PLoS One. 2013;8.

-

Castricini R, Longo UG, De Benedetto Chiliad, Panfoli North, Pirani P, Zini R, et al. Platelet-rich plasma augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:258–65.

-

Pandey 5, Bandi A, Madi Southward, Agarwal L, Acharya KKV, Maddukuri S, et al. Does application of moderately concentrated platelet-rich plasma improve clinical and structural outcome after arthroscopic repair of medium-sized to large rotator gage tear? A randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25:1312–22.

-

Antuña S, Barco R, Martínez Diez JM, Sánchez Márquez JM. Platelet-rich fibrin in arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomized airplane pilot clinical trial. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79:25–30.

-

Kesikburun Southward, Tan AK, Yılmaz B, Yaşar E, Yazıcıoğlu K. Platelet-rich plasma injections in the treatment of chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2609–16.

-

Rodeo SA, Delos D, Williams RJ, Adler RS, Pearle A, Warren RF. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin matrix on rotator cuff tendon healing. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1234–41.

-

Weber SC, Kauffman JI, Parise C, Weber SJ, Katz SD. Platelet-rich fibrin matrix in the management of arthroscopic repair of the rotator gage. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:263–70.

-

Randelli P, Randelli F, Ragone Five, Menon A, D'Ambrosi R, Cucchi D, et al. Regenerative medicine in rotator cuff injuries. Biomed Res Int. 2014.

-

Barber FA, Hrnack SA, Snyder SJ, Hapa O. Rotator gage repair healing influenced by platelet-rich plasma construct augmentation. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2011;27:1029–35.

-

Dhillon MS, Patel Due south, John R. PRP in OA knee - update, current confusions and future options. SICOT-J. 2017;3:27.

-

Pifer MA, Maerz T, Baker KC, Anderson M. Matrix metalloproteinase content and activity in low-platelet, depression-leukocyte and high-platelet, high-leukocyte platelet rich plasma (PRP) and the biologic response to PRP past human ligament fibroblasts. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1211–8.

-

Riboh JC, Saltzman BM, Yanke AB, Fortier Fifty, Cole BJ. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee joint osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:792–800.

-

Cross JA, Cole BJ, Spatny KP, Sundman E, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP, et al. Leukocyte-reduced platelet-rich plasma normalizes matrix metabolism in torn human rotator cuff tendons. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2898–906.

Acknowledgements

At that place are no funding sources to report linked to the completion of this work.

Authorship

All named authors: Jack Hitchen (JH), Nicholas Thousand Wragg (NMW), Maryam Shariatzadedeh (MS ad Samantha L Wilson (SLW) run into the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, have responsibleness for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their blessing for this version to be published. All authors have contributed significantly, specifically; JH, NMW, MS, and SLW were all involved in conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and estimation of literature for the work presented. JH and SLW were all involved in drafting the work; NMW and MS were involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given their final approval of the version to exist published and are accountable or all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the piece of work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Conflict of Involvement

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, commercial, or of other association.

Upstanding Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by whatever of the authors.

Informed Consent

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not comprise any studies with human participants or animals performed by whatsoever of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and betoken if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this commodity are included in the commodity's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is non included in the article's Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Hitchen, J., Wragg, North.M., Shariatzadeh, One thousand. et al. Platelet Rich Plasma as a Handling Method for Rotator Gage Tears. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2, 2293–2299 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00500-z

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s42399-020-00500-z

Keywords

- Musculoskeletal injury

- Platelet-rich plasma

- Standardisation

- Re-tear

- Rotator cuff tear

schillersains1999.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42399-020-00500-z

0 Response to "Prp Injection for Rotator Cuff How Do You Know if You Are Healing"

Post a Comment